It was autumn in Milwaukee. Things were dying already.

That made it easier, somehow.

Madison and Patrick were running late for Laurie’s birthday party. Classic them, right? Patrick’s excuse last time was the board meeting. His excuse the time before that was the meeting with the VC firm. Now his excuse was the meeting with his cofounder, who had offered—one of those offers that isn’t really an offer—to buy Patrick out of the company.

This was something of a pattern with Patrick. He had big, exciting ideas but no business sense or practicable skills like sales or coding or graphic design. He was also too gentle a person. He believed if he was fair to people, people would be fair to him.

So he’d pitch a new venture, get no shortage of interest from partners and investors, then have his idea yanked out from under him.

Every time it happened, Madison helped him hold a funeral in the backyard. They didn’t dig up actual dirt or put up actual headstones. It was only ceremonial; there were no bodies. Patrick would say a few words, blow out a candle, then they’d walk hand in hand back up to the house.

Patrick and Madison had three acres just west of the city. A better way to say that would be Patrick had three acres, which Madison had recently moved onto. His failed businesses were pretty lucrative, as far as failures go. They’d bought him a columned front porch and one of those softly winding staircases you see in movies about prom night. His backyard was a mix of silver maples and northern red oaks that lit up for six weeks each year before being extinguished by winter.

Even though Patrick technically owned his three acres, it was Laurie who decided what went where.

Laurie was the president of the neighborhood HOA. She lived seven houses down in a Tudor Revival with four chimneys. That she was so close made it almost inevitable Madison and Patrick would be late for her party. It’s easy to be late when you don’t have far to go. You think you have so much time, and you get careless.

Which is more or less how Madison ended up forgetting the gift.

“Shit,” Patrick said, staring into the phone his soon-to-be former cofounder’s voice had just stopped coming out of.

Then, “Shit,” he said again, when Madison told him about the gift.

“Sorry,” she said. “I lost track of time again. Can’t we bring a bottle of wine or something? It’s weird enough we’re going. It’s not like we’re friends.”

Patrick sighed. “I know. I’m this close to getting her to sign off on the heated driveway though.” He paused. “I don’t think I can convince Aaron. He has some good points anyway. Maybe I’m not cut out for this.”

Madison took Patrick’s head between her hands, steered it till he met her eyes. “What am I going to say?”

Patrick chewed his lip.

“C’mon.”

“You’re going to say fuck that guy.”

“Right. Fuck that guy. You’ll come up with something else. You always do.” She dragged a knuckle along each side of his jawbone like her two brief months of massage therapy school had taught her to do.

They sat at the waterfall kitchen island in silence, Madison slouched against Patrick’s chest, listening for his heartbeat to slow.

They were already late for Laurie’s. What was a few minutes more? Patrick said if the heated driveway didn’t work out this year, they could always try for a firepit. The Kiesslings had one. He joked that with the firepit they could do cremations instead of burials, scatter the ashes of his failed businesses across the blues of Lake Michigan.

Outside the window, everything was dying.

The leaves were dying. The fall color tour, this far north, was over, and what little foliage was left on the trees was a curling, muted brown.

The day was dying. It was four o’clock on a Saturday and already the sun looked ready to call it, tired of fighting the Corn Belt’s impenetrable haze.

The year was dying. Madison couldn’t remember how long she’d been wearing this particular house cardigan. She used to differentiate between her house cardigans and her outside-the-house cardigans, but at some point one category swallowed the other, a kingsnake devouring a helpless rattler.

Patrick’s hopes for his business were dying.

His hopes for a magic snow-melting driveway were dying, as the afternoon ticked callously onward.

In Las Vegas, where Madison was from, you could take yourself down to the nearest windowless casino and walk endless laps, like looking for your lucky slot machine, and simply not engage with the passage of time.

In Milwaukee, though, things died and they announced themselves. They set it up so they were framed perfectly in your kitchen window to take their final wheezing breaths.

“Huh.” Madison leaned forward to see better. “What is that?”

“Is it dead?” Patrick asked once they were in the backyard, a pair of teal rubber gloves drooping from each fist. “Don’t touch it, Mad, Jesus. Those things carry diseases.”

Madison crouched beside the young bat. The lawn was green but bristly, and the bat sort of rode on top of the grass rather than sinking into it. She remembered that game, “Light as a Feather, Stiff as a Board.” She imagined the blades of grass as held-out fingertips wanting to believe.

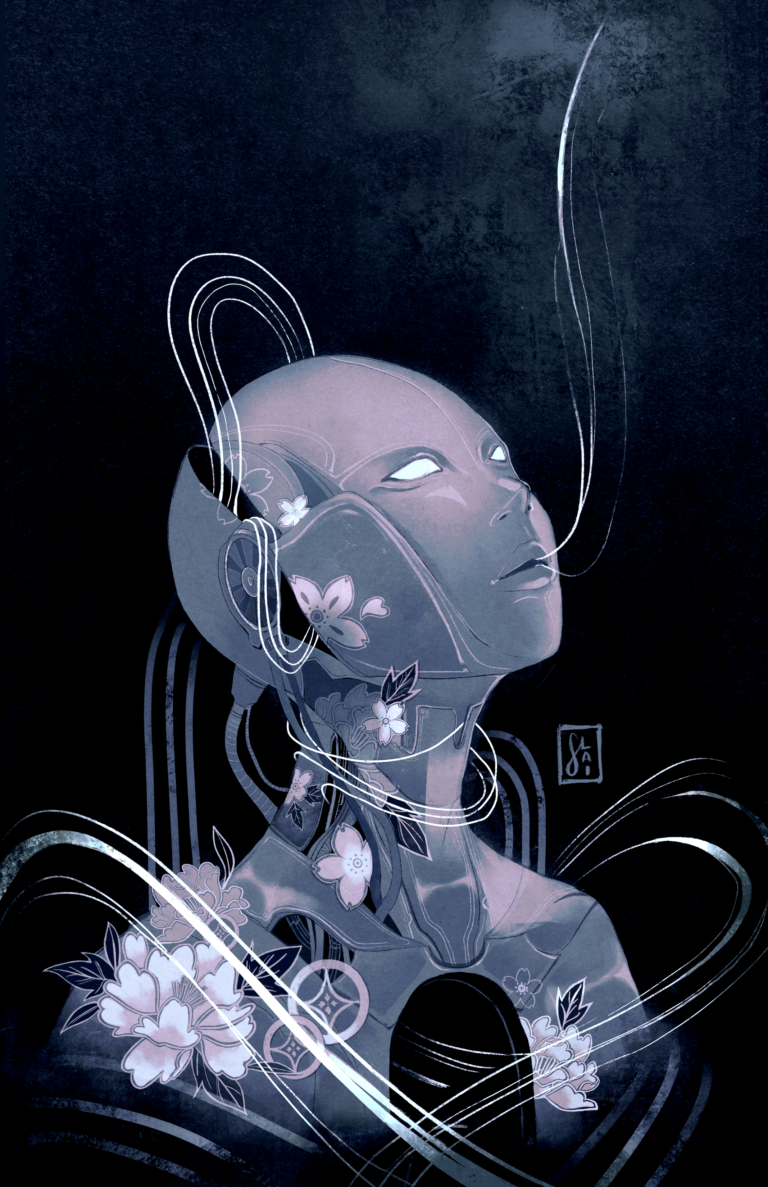

The bat was brown with a black snout and black ears. Its wings looked like one of Leonardo da Vinci’s flying machines, and its hands and feet were startlingly human. It was tiny, very cute, ancient-looking. Madison had never seen one so still and so close.

“It’s just a baby,” she said. Then, “Why’s there a baby this time of year?”

“What do you think killed it?” Patrick looked the bat over. It didn’t have a scratch on it. No gouged-out bits from the talons of a hawk or owl. No tooth marks from a neighborhood dog. “You don’t think it flew into the window?”

Madison shook her head. “Probably pesticides, right? Or it just fell.”

The young bat looked made of velour. It was the exact color of the Dollar Tree teddy bears that smell like chocolate. Its wings were thin and fragile, peach-fuzzed.

Patrick tapped his chin. “Hey,” he said slowly, casually. “Isn’t Laurie into bats?”

Madison shrugged. “She’s definitely into Halloween.”

“No kidding. Did I tell you she changed the rule about lawn decorations? When Tyler was in charge, they couldn’t be more than six feet tall.”

“Her inflatable Frankenstein has to be, what, double that?”

“Right? And we can’t even paint the door.”

They laughed then, but their laughs were hollow, seemed to spring from the enamel of their teeth instead of from their throats. They weren’t looking at each other, either. Madison was looking at the bat, half expecting its wings to unfurl, its little brown belly to rise. Patrick was looking at his watch.

“So,” he said finally, “I have this idea.”

Madison raised a brow.

“What?” Patrick held up two rubber-gloved palms. “It’s already dead. We have to bring something. Besides, I genuinely think she’ll like it. She can put it on the mantel with all her other spooky tchotchkes.” He added, “Wouldn’t it be kind of satisfying? Obviously it’ll be our secret, but she’ll basically be displaying roadkill.”

“It’s not roadkill!” Madison made her hands into a protective dome around the baby bat. She stroked the air an inch above its head.

“I guess you’re right though,” she admitted, about the customary birthday gift. And about it being pretty satisfying, yeah: putting a literal skeleton in the closet of Laurie McKellen’s catalog home.

Plus, Patrick’s earlier point about diseases. They would have to handle the bat eventually, couldn’t just leave it there to rot and attract predators, further links in a potential global outbreak chain. This was one way to guarantee any contagions would be safely locked away.

Madison watched the soft brown fur for the slightest flutter. When there was nothing, and still nothing, she turned the bat to stone.

Well, she turned the bat to faux marble.

It had the veining of the real thing, but the colors were less subtle. If you spent enough time with it, you’d notice the striations repeated in a predictable pattern—instead of branching out randomly, organically, like happens with mineral deposits in natural stone.

The faux marble bat felt wrong in Madison’s hand. “Do you think it’s too light?” she asked Patrick.

Without holding it himself, he assured her, “No. No way. Look at it. It’s so small.”

Madison hadn’t always had the power. She’d developed it after moving into Patrick’s big house in the burbs.

She used to live on the other side of Milwaukee, in a sweet, somewhat run-down rental across from a twenty-four-hour Arby’s. She was always shoving down a sausage biscuit or potato cake on the way to the fancy climbing gym where she worked reception, and where members were the kind of buff and spindly that meant they’d never seen a potato cake in their lives.

That’s where she met Patrick.

She was toggling between the class scheduler and the websites of a few different massage therapy schools. She was still in the research phase then. She would quit her job when she moved in with Patrick, drop out of school shortly after, right in the middle of a unit on the anatomy and physiology of the lymphatic system.

He told her he wanted to take care of her. She’d spent her entire adult life and some years before it working odd jobs, stringing paychecks together on a thin, fraying line. He wanted her to be comfortable. Relaxed.

What she was instead was bored.

After the initial shock of relief rolled through her, stability turned out to be boring. The suburb was boring. The house was boring. Sleeping in late was boring, and worrying about which hobbies she should take up, what would be meaningful and not too expensive—thinking in pennies was a tough habit to break, no matter what Patrick said—was tiresome. The drama with Laurie was only noteworthy because it was a shade less boring than everything else.

Madison began to lose track of time. Every day felt like the last one, the next one. She felt her brain atrophying.

And something funny happened in there, in the space between the freshly shrunken tissue. Some kind of rearranging. One day Madison was scrubbing the sink, thinking hard, heavy, sharp-cornered thoughts, when, lo and behold: the dish sponge turned to stone.

Well. Faux marble.

With a green base, yellow veining. The gloss artificial enough to give it away.

But the novelty quickly wore off, and even her new power was boring. What good was turning things to stone, really, when she couldn’t turn them back? There wasn’t much she wanted to be stone that wasn’t stone already. Patrick’s staircase was real marble shipped in from a quarry in Vermont. His kitchen island was a slab of quartz that glimmered in the recessed lighting. His house was polished limestone, done in the Mediterranean style.

Madison could turn most objects into a heavier version, that’s all. Her specialty was free weights. She told Patrick he could cancel his gym membership: she’d made it so the ficus weighed two hundred pounds.

She was in the shower one morning, thinking shower thoughts and letting her eyes unfocus, when she accidentally made the showerhead faux marble. Then she panicked and, before she could stop herself, she made the water faux marble. All the way down to the pipes.

The plumber said he’d never seen anything like it. After that, Madison was afraid to let herself go again, end up with a useless stone flat screen or a Flintstones-style Volvo in the drive.

Laurie sure as hell wouldn’t approve of that.

The bat sculpture was a hit. Madison and Patrick used a couple sticks to pose the baby before Madison turned it, so it wouldn’t be stuck forever in its scared, dying-motherless form.

Laurie ran her thumb over one of the leaflike ears appreciatively, said it looked so real.

She still denied Patrick’s heated-driveway proposal. But the couple noticed she became more lenient, didn’t raise a stink every time they failed to wheel the empty trash bins back into the garage the millisecond after pickup.

Madison counted that a win, and she didn’t think about the little bat again.

Until Patrick’s parents called to complain about their contractor.

Patrick’s parents lived in New Mexico, in a sprawling gated community that once a year opened to the public for a ticketed home and garden tour.

To prepare for this year’s tour, they were having their landscaping updated, a few new features put in. Well, the contractor had delivered the burbling fountain, and he’d finished the terracing and the arched gnome bridge. But as for the pair of guardian lions they’d ordered? He came back and said the lead time was longer than he’d anticipated. Realistically, he wouldn’t have the lions till spring.

This devastated Patrick’s mother, who’d envisioned the garden features as a matching set. The fountain looked stupid without the lions, she said.

And Patrick, who only wanted to please his parents, who was always and forever paying for the criminal offense of moving away? Patrick offered to help.

“Why don’t they just buy some lions?” Madison asked.

Patrick shrugged. “They’re not just any lions. Remember that Danube river cruise they went on? Ma saw these sculptures on some bank or theater. Part lion, part bird, part…something else, I can’t remember. She’s obsessed with them. I swear she would’ve ripped them off the building if she could’ve.”

“Does she have a photo? They could commission an artist. I mean, it’s Santa Fe. Not like they can’t afford to.”

“For sure, for sure.” Patrick bit his lip. “Just, they really wanted everything to be ready in time for Desert Splendor. You know they took last year off, with Dad’s heart thing…”

Madison watched his leg bounce, settled a hand on it. “Okay, but what am I supposed to do? That’s pretty specific. It’s not like a part-lion-bird-whatever is just going to drop dead in your backyard.”

Patrick’s eyes lit up. “Our backyard,” he said. Then, “Leave it to me.”

When Patrick came home with a dead cat and a paper bag from PetSmart—inside: one of those adjustable costume manes, a set of feathery angel wings — Madison wasn’t convinced. But that was the thing about Patrick. He had big ideas. He knew how to make something from nothing, how to get people excited.

And he was gentle, Madison had always thought so. Not so gentle that he wouldn’t scour the back roads and neighborhood Nextdoor threads hunting for animal carcasses, but still.

Guardian lion number one was a test run. They propped the cat against the staircase’s bottom step till it was sitting on its haunches, then put a couple books in front to keep the paws from sliding out.

It looked ridiculous to start with. Cheap, clearly flammable materials. Too haphazardly mixed media. But once Madison turned them into one solid hunk of faux marble, the pieces hung together well enough.

The trick, Patrick said, was finding a body that didn’t look collapsed, or have bone piercing through skin, or bear visible tire tread. When he found the dead calico out by 94, its mouth had been hanging open, its pink tongue lolling out. It was a nice effect. In an upright posture, it gave the impression of a growl.

The next day Patrick resupplied, and Madison turned a second statue.

She worried the faux marble would clash with his parents’ house, which, like a lot of houses in that part of Santa Fe, was a big-windowed modern adobe. It was pure luck the lions ended up a creamy off-white with peach veining. She didn’t have much control over color.

The cost to ship them must’ve been outrageous. Madison forgot to ask. Every time she turned something to stone, the fast-surfacing electric heat behind her eyes caused her migraines to flare up for a week.

In her dreams, her head was too heavy to hold up.

In her dreams, her head was bleeding: a manic den of coiled muscle writhing, choking itself out.

Someone else would’ve opened an Etsy shop and made a whole series of bat sculptures, then a mouse series, a bunny series—some wearing hats and sweaters, probably. Nonliving things, too: items for dollhouses, dioramas. People love miniatures. There’s a huge market for collectors.

Someone else would’ve joined Habitat for Humanity. Would’ve helped so many desperate people, turning corrugated tin walls and thatched roofs into sturdy, weatherproof stone.

Someone else would’ve made a firepit without asking for Laurie’s permission. What was Laurie going to do anyway? The grandest firepit in the neighborhood, and it would’ve popped up overnight.

But we’re talking about Patrick here.

When the word got out about the couple’s statuary, they took on a handful of small projects at first. Gifts and favors, mostly. What Patrick called good practice. Faux marble doves for Madison’s sister’s wedding in Dallas. A smattering of faux marble firs, each one a dramatic statement in a vaulted living room at Christmas.

And Madison wasn’t bored anymore. She was drained after another turning, or she was disgusted waving fat flies off Patrick’s most recent harvest, or she was happy reading a thank-you note from another satisfied customer. But she wasn’t bored.

It felt right having a job to do.

Patrick was rubbing her shoulders, trying to get to the root of the shooting pains that started sometime around the third faux marble fir. His thumb found the juicy spot on her neck.

“You’re better at this than I ever was,” she was saying when his phone rang.

It was Aaron, his former business partner.

Patrick picked up on reflex. The men did awkward small talk for all of forty seconds before easing into it, like no time or past hurts yawned between them, like they were still buddies at Booth. That was Patrick for you. He had no knack for holding grudges. He hadn’t given up hope for a fairer, kinder world.

Aaron had seen the posts. Turned out Laurie was a family friend, or an ex’s ex, something. He wanted to know how it worked. Did Patrick have some massive 3D printer? How did he get them to look so real? And how much fundraising had he done? Did he have plans to scale?

Patrick shot Madison a caught-in-headlights look. She started shaking her head, but the pulsing was so intense she had to stop.

Patrick didn’t tell Aaron everything right then, but he did admit the stone was faux marble.

Aaron’s voice was crackly on speakerphone. “Smart,” he surprised them by saying. Then he chuckled. “Everything’s fake these days anyway.”

Later, Patrick fessed up to everything. Except for the exact details of Madison’s power, which he just called “proprietary technology.”

Now it was Aaron who had the ideas. The possibilities were endless, he said.

On the lower end: a new kind of taxidermy. A little less redneck uncle’s basement, a little more friendly for the foyer. Classy, but authentic, the admired thing still firmly ensconced inside.

On the higher end: Memorials. Monuments. Commissions on the state level, the national level. Aaron said he was just spitballing here. There were a dozen more audiences they could explore.

He told Patrick, “Today, that market segment is primarily addressed by individual artists. We’ll be cheaper, more straightforward, more repeatable. We’ll be able to handle any order, even bulk orders, on an expedited timeframe that artists simply can’t swing, and for a fraction of what they’d charge. Plus, we’re hyperlocal. We wouldn’t be outsourcing to overseas factories. We can do it huge and we can do it here, in the good ol’ USA.”

“In the country, too,” Aaron added. “America’s Heartland. Doesn’t get more idyllic than that.”

Patrick hesitated. “We’re in Milwaukee.”

“Absolutely. They’ll love that.”

“They?”

“One thing, though. Again, I’m just spitballing, but if the product looks that lifelike built on, what was it, a dead bat? Imagine how great it’d look if the foundation’s alive. Don’t worry about that now. Ethical can of worms. We’ll get a team on it.”

When Patrick recounted all this to Madison, she was only half-listening. She couldn’t stop thinking about Santa Fe. The two faux marble lions sitting there, atop vast reserves of turquoise.

That summer, Patrick and Aaron launched Marblio.

Early investors said the venture had a ton of promise. The only fault they could find in the initial pitch, really, was the name Patrick had proposed.

Medooz.

Too harsh-sounding, they agreed. One investor thought it sounded like a sleep aid. Another said it made him think of Medjool dates. Not sexy.

The company’s logo wasn’t a bat because Batman and DC Comics have a monopoly on bat and bat-adjacent iconography, pretty much. But the way the font was done, the logo’s pointy “M” still reminded Madison of that baby bat’s enormous, translucent ears. Listening from that crowded mantel seven houses away, and hearing all she had done and was still doing.

Listening from Laurie’s.

She was part of the official partnership agreement, Laurie was. The deal was Aaron would talk to Laurie about getting the heated driveway approved, put in a word for his dear pal Patrick.

The other terms of the agreement were solid—Patrick had learned his lesson, hired two lawyers to check it over—but what really put it over the edge was the driveway. A snow-devouring web of hydronic radiant heat under four-inch-thick concrete.

Madison didn’t get it. Wasn’t snow the one good part of winter? It was like the gods had sent the clouds down so mortals could have a turn playing in them. Snow covered all the ugly brown decay in a bright white gleaming. It was a blanket over the expansive casket of the dead.

But Patrick said, “Shoveling is such a time suck. Unless you want to spend a quarter of the year digging the cars out?”

“Want” had little to do with it. By this point, Madison was depleted. She’d stopped suffering from headaches, plural, and instead knew only the single, fused-together, unending, ponderous ache. Her spine was razor blades, her brain sparking steel wool.

She laid in a dark room alternating between heat pack and cold compress. Patrick brought tea, pills, ginger chews. He brought peppermint essential oils. She was too tired to tell him she hated the fragrance. It made her universe smell like mouthwash.

Most afternoons, Patrick drew the curtains in the living room and dollied in Marblio’s latest commission. He took Madison’s head between his hands and steered it, just like she used to do for him.

To turn a faux marble monument, a custom headstone.

The bust of a respected thinker for the presidential garden.

Six busts, a dozen.

She could hardly see what she was doing. He held her eyes steady. Still, her work got shoddy, everything flattened: the details muddled and the textures too smooth. The fingers were never quite right. There was something off about the ears and teeth. She’d never finished that anatomy unit, was the problem. She’d always relied on existing materials she could build on top of.

Even with those slipups, Marblio’s customers couldn’t argue with the speed, the price. The company’s stock went up, up, up.

Patrick kept Madison as comfortable as possible. He kept her relaxed. After she lost her ability to see color, he described the hues of each finished piece, its veining, in exhaustive detail.

And yet, sometimes, at the furthest distance from one of Patrick’s heady cups of tea, Madison would feel something deep within her brewing. Beneath the dense sludge that clogged her senses now, there was a fathomless well that no one could all-the-way seal up. Least of all a measly, boring human.

Patrick kept a wet cloth over her eyes. For the headaches, he told her. It was plush like a towel, but tied tight at the back like a blindfold. She felt the knot in the loose notch between her neck and skull.

The fibers rasped against the whites of her open eyes. Her eyes rasped back against the cloth and, quietly, it squealed.

“Scathing” doesn’t begin to describe the look she gave Patrick.

The look she gave him, behind that wearing-thin cloth?

It was the kind that turns a man to stone.

Drew Broussard

Drew Broussard Duane Horton

Duane Horton Glenn Dungan

Glenn Dungan

Jill Feenstra

Jill Feenstra Kristina Ten

Kristina Ten LeeAnn Perry

LeeAnn Perry

Hello! My name is

Hello! My name is  Zeke Jarvis

Zeke Jarvis